The Mozart Requiem is one the best-loved of all choral works. It was secretly commissioned in July 1791 by Franz Walsegg, an Austrian Count who wished to pass the finished work off as his own. After Mozart died in December 1791, with the work in a fragmentary state, his widow Constanze needed to get the Requiem completed in sufficiently credible form to convince Walsegg it was indeed by Mozart: payment of the second instalment of the handsome fee depended on this. It was finished by Franz Süssmayr – not necessarily the best composer available, but he had discussed the piece extensively with Mozart, and was a quick worker. Even better, he could mimic Mozart’s handwriting and signature. It was done, amazingly, within two months and subsequently presented to Walsegg. Walsegg performed ‘his” Requiem two years later at an out-of-town location, but not before it had already been performed in Vienna as a work of Mozart’s. Walsegg took legal action when the Requiem was finally published in 1800 under Mozart’s name not his. He eventually came to an out of court settlement with Constanze.

Salieri had nothing whatsoever to do with the composition of the Mozart Requiem – the scenes of him taking musical dictation from Mozart in the Amadeus film are entirely fictitious (like a number of the scenes in this brilliant film). He didn’t poison Mozart either. Mozart was not buried forgotten in a pauper’s grave – his burial arrangements were entirely in accordance with established practices and hygiene regulations in Vienna at this time, and there was a funeral ceremony in St Stephen’s Cathedral, at which the Requiem and Kyrie choruses of the Requiem were probably performed, only a week after his death. Salieri was in the funeral procession.

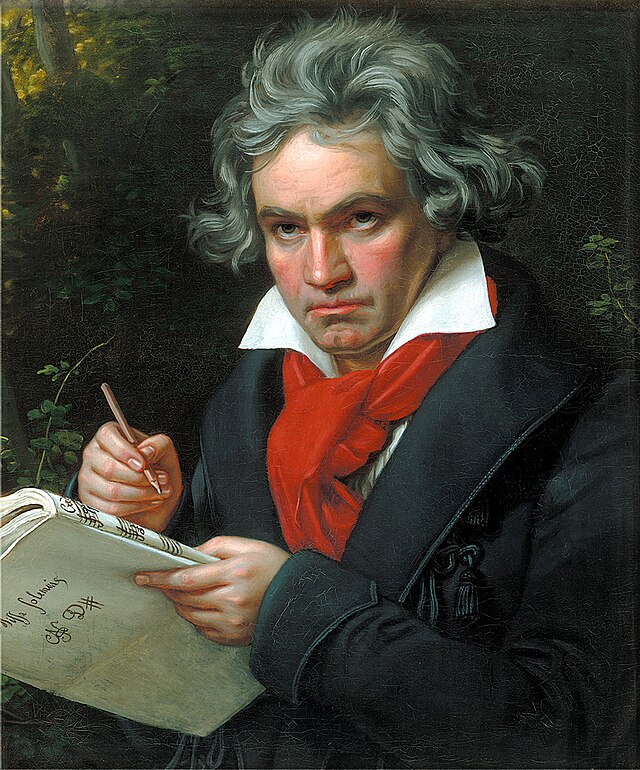

The Choral Fantasia was first performed at a four-hour long concert in Vienna in 1808 – “the most amazing concert in history” – which also featured the premieres of two Beethoven symphonies – nos 5 and 6, plus his fourth Piano Concerto. It was a freezing cold night in Vienna, and the heating in the theatre had broken down. The orchestra ground to a halt in the Choral Fantasia because of confusion over repeats (the piece had only been completed on the morning of the concert). Beethoven was conducting, but as he was by now almost completely deaf, it took some time for him to realise that something was up. The frozen audience was completely bamboozled in trying to take in all these ground-breaking pieces one after another. The Fantasia is rarely performed by amateur choral societies – it will certainly never have been heard in Ambleside! – but makes a brilliant ending to the concert.